Another truly significant person from Turner Station was Mrs. Henrietta Lacks, a classic World War II era Turner Station woman. She was married to a steelworker, living with her family at 713 New Pittsburgh Avenue. She had moved to Turner Station from Clover, Virginia when her husband took a job at the Bethlehem Steel plan at Sparrows Point. In 1951, after visiting Dr. William Wade in Turner Station, she was referred to Johns Hopkins hospital for tests….Henrietta’s family knew nothing about the great medical Accomplishment until 1969. (37)

Kelly, Jacques. The Baltimore Sun

Roberts, Dorothy. Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics, and Big Business Re-Create Race In the Twenty-First Century.

In her work Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics, and Big Business Re-Create Race in the Twenty-First Century Dorothy Roberts explains:

“Before Henrietta Lacks died of cervical cancer in 1951 in a colored “clinic patient” ward at the Johns Hopkins charity hospital, a doctor cultured the cells from her cervix without her consent. Her cells, known by scientists as HeLa, had the amazing ability to reproduce endlessly and prolifically, providing material for more than sixty thousand scientific studies that contributed to a wealth of medical advances from the polio vaccine to chemotherapy and in vitro fertilization. While the HeLa cells enabled a lucrative biomedical industry, the Lacks children, who were not informed for decades about the fate of their mother’s tissue, struggled with inadequate health care. The injustice is capture in the words of Lacks’s daughter: ‘I would like some health insurance so I don’t got to pay all that money every month for drugs my mother’s cells probably helped make.’ The story of Henrietta Lacks reflects the horrible history of medical exploitation and neglect of African American that has been reinforced by the view that their bodies are intrinsically inferior. But her story also defies the belief in inherent racial differences. Her cells, although they came from a black woman, helped to improve the health of human beings the world over and testify to our common humanity” (103).

Rogers, Michael. “The Double-Edged Helix.” Rolling Stone, March 25, 1976, 48-51.

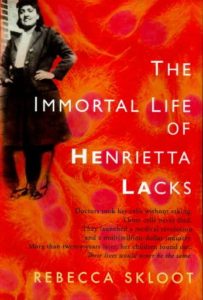

Skloot, Rebecca. The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.

• Skloot, Rebecca. “Enough with Patenting the Breast Cancer Gene,” Slate’s Double X (2009)

• Skloot, Rebecca. “Taking the Least of You, ” The New York Times Magazine (2006)

• Skloot, Rebecca. “Henrietta’s Dance,” Johns Hopkins Magazine (2000)